The final two years of Beethoven’s compositional career — and hence these last few weeks of December — are dominated by 5¼ string-quartet masterpieces, with only scattered tiny canons and piano trifles in between to allow us to catch our breath and not be totally overwhelmed.

For lovers of chamber music, the greatest letter in the history of music was addressed to Beethoven on 9 November 1822. Here’s how it appears in Thayer-Forbes, p. 815:

Monsieur!

I take the liberty of writing you, as one who is as much a passionate amateur in music as a great admirer of your talent to ask if you will not consent to compose one, two or three new [string] quartets for which labor I will be glad to pay you what you think proper. I will accept the dedication with gratitude. Would you let me know to what banker I should direct the sum that you wish to get. The instrument I am cultivating is the violoncello. I await your answer with the liveliest impatience. Could you please address your letter to me as follows:

To Prince Nicholas de Galitzin at S. Petersburg care of Messrs. Stieglitz and Co. Bankers.

I beg you to accept the assurance of my great admiration and high regard.

Prince Nicholas Galitzin

Beethoven had been making sketches for a new string quartet as early as May 1822, so this letter became a catalyst to turn those sketches and ideas into compositions. On 25 January 1823, Beethoven accepted the commission.

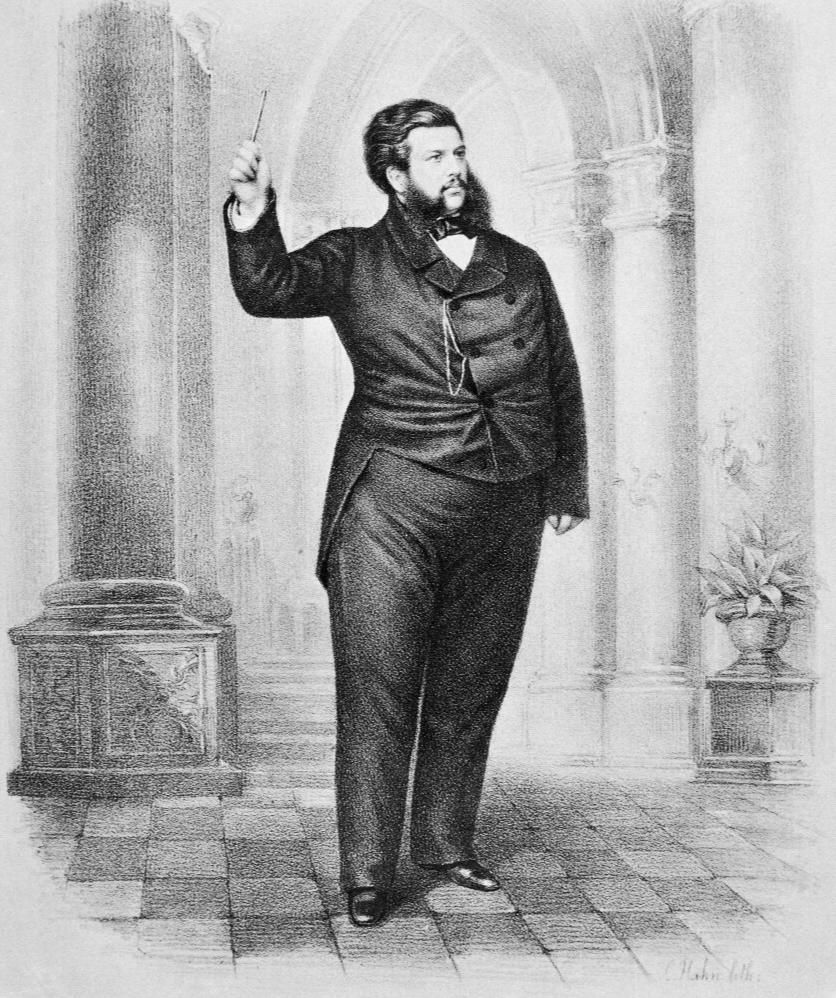

Prince Nicholas Galitzin was not yet 28 years old when he wrote the letter to Beethoven commissioning one, two, or three string quartets. He had been introduced to Beethoven’s music by Ignaz Schuppanzigh (Day 142) during his visits to Russia.

For much of 1823, the highest priority for Beethoven was completing the Ninth Symphony. Over a year after Prince Galitzin’s first inquiry, he wrote Beethoven on 29 November 1823:

I am really impatient to have a new quartet of yours, nevertheless, I beg you not to mind and to be guided in this only by your inspiration and the disposition of your mind, for no one knows better than I that you cannot command genius, rather that it should be left alone, and we know moreover that in your private life you are not the kind of person to sacrifice artistic for personal interest and that music done to order is not your business at all. (Thayer-Forbes, p. 924)

The first of the three string quartets commissioned by Prince Galitzin was not ready until February 1825, but in the interim, the Prince arranged for the first full performance of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, which occurred in St. Petersburg on 18 April 1824.

Maynard Solomon writes:

It was an opportune time for Beethoven’s string quartets to come into existence. In eras when the major avenues of communication are controlled by censorship, and an apathetic public tends to utilize art primarily for hedonistic gratification, serious art flees to the margins of society and to the more intimate genres, where it sets up beachheads in defense of its embattled position. Artist and audience rise to defend the sanctity of art at those moments when its social function has become endangered and its aesthetic and ethical purpose called into question.

Such was the case in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, with the breakdown of traditional aristocratic patronage and the erosion of Enlightened attitudes towards the arts. Beethoven’s late works seem to have crystallized avant-garde currents among Viennese intellectuals. Audiences isolated from traditional means of patronage and opposed to normative tastes began to take shape. … Drawn from many walks of life — artists and writers, musicians and music lovers, bankers and merchants, along with the remnants of the old connoisseur aristocracy — this audience worshiped Beethoven (not uncritically) and his music as the stalwart symbol of better days past and to come. (Beethoven, p. 415)

Unlike Beethoven’s late Piano Sonatas, the late String Quartets were not published in the order that they were composed, and hence they not numbered chronologically. Here’s the basic list in chronological order showing the approximate dates of completion:

No. 12 in E♭ Major, Opus 127, February 1825

No. 15 in A Minor, Opus 132, July 1825

No. 13 in B♭ Major, Opus 130, November 1825

No. 14 in C♯ Minor, Opus 131, July 1825

No. 16 in F Major, Opus 135, October 1826

The only one that’s really out of sequence is Opus 132.

However, there are additional complexities: Opus 130 received a new final movement in November 1826, and the original finale (the Grosse Fugue) was published separately as Opus 133, and for piano four-hands as Opus 134.

Of these works, only Opus 127 was published during Beethoven’s lifetime by Schott. The rest were published posthumously in 1827:

- Opus 130, 133, and 134 by Artaria

- Opus 131 by Schott

- Opus 132 and 135 by Schlesinger

The missing opus numbers in this sequence are Opus 128, which is the song “Der Kuss” (Day 331) and Opus 129, the Rondo “Rage Over a Lost Penny” (Day 53) composed in 1795 and published by Anton Diabelli in 1828.

In his book The Beethoven Quartets, Joseph Kerman writes:

One is carried away, astonished, and ravished by the sheer songfulness of the last quartets — by recitative and aria, lied, hymn, country dance, theme and variations, lyricism in all its manifestations. The first of the series of late quartets, the Quartet in E♭, Op 127, is of all Beethoven’s works his crowning achievement to lyricism. (pp. 195–6)

It is conventionally structured with four movements, the middle two being an Adagio and Scherzo.

#Beethoven250 Day 343

String Quartet No. 12 in E♭ Major (Opus 127), 1824–25

The Merel Quartet (@MerelQuartet) in a lived-streamed concert from a church in Zurich during summer 2020.

Opus 127 proclaims its arrival with a six-measure Maestoso that seems like an introduction to the first movement, but which strategically appears twice more in different keys and stretching further in pitch, the third time with a twelve-note chord that spans four octaves.

The first-movement Allegro of Opus 127 is a lyrical wonder — tender, wistful, intimate, with themes being passed contrapuntally among the instruments, and drifting through moods of occasional agitation and quiet repose, ending with a whisper.

The heart of the Opus 127 quartet is the second-movement Adagio, in performance about twice as long as the other movements. It’s a theme with variations that unfold so organically that there is disagreement precisely how many variations there are.

The theme itself is in 12/8 time, beginning like a canon but blossoming into a long, winding melody, first in the violin and later the cello. The first variation is easy to miss because it’s also in 12/8, but it comes right after the strings play three quiet chords. The melody is elaborated, sixteenth notes are introduced, and more chromaticism.

A few more isolated chords, and then the start of Variation 2 is obvious: a switch to 4/4 Andante and a gay jaunty dancing rhythm.

Variation 3 is signaled by a sudden shift back to a gorgeous hymn-like Adagio.

Variation 4 returns to 12/8, the first violin and cello weaving entrancing melodies, with the rhythm almost like Variation 2, but more subdued.

As Variation 4 trails off into sparseness and three pizzicato notes, let’s call it Variation 5 emerges, although it’s really only a half variation, and possibly just an interlude.

Violin trills signal the start of Variation 6, but where the coda begins, who knows?

(Following Beethoven’s death, many musical tributes were published. “Beethoven’s Heimgang” — or “Beethoven’s Passing” — is a song fashioned from the opening of the Opus 127 Adagio, with a text that assures us that he’s in a better place).

Four pizzicato chords introduce the Scherzandro. Ever since replacing Minuet movements with Scherzos, Beethoven had sometimes been reluctant to label his scherzo movements with that word when the joking aspect of the traditional scherzo was not quite appropriate.

But for the Opus 127 String Quarter, he has no such reluctance. It’s similar in a couple ways to the Scherzo of the Ninth Symphony (Day 336). It has that same kind of driving rhythm, the same pseudo-fugal textures, the same kind of melodies that emerge from the repetitive patterns, and similar long repeats.

The highly contrasting Trio section is marked Presto and seems like a steady flow of quarter notes but out of which emerges a hoedown.

Also similar to the Ninth Symphony Scherzo, it seems as if we’ll get another repeat of the Trio and Scherzo for a five-parter, but Beethoven reconsiders and wraps it up with a satisfying crescendo conclusion.

In its simplicity, directness, and folksong-like tunefulness, the Finale of Opus 127 totally enchants, punctuated with occasional hard-edged double-stopping and foot-stomping peasant dance rhythms. A couple of violin trills introduce an extended 6/8 Allegro coda where the music ascends into magical ethereal regions, ending with a coda within a coda.

The coda is a telling example of Beethoven’s sensitivity to the effects of harmonic shift and tone color. Anticipating Impressionism by three generations, it blends the strings in a gossamer web of new sonorities, some of which were heard by Schubert and used to wonderful effect in his last piano trio, in the same key, and in his own late quartets, written in the next few years.” — Lewis Lockwood on Opus 127, Beethoven, p. 452

#Beethoven250 Day 343

String Quartet No. 12 in E♭ Major (Opus 127), 1824–25

The Curtis Institute of Music-based Dover Quartet (@DoverQuartet) in an enchanting performance.

The first performance of Beethoven’s Opus 127 on 6 March 1825 did not go well. It was performed by Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who had returned to Vienna by 26 April 1823 (Day 335) and formed a string quartet with Karl Holz as 2nd violin, and two players from the old Razumovsky Quartet (Day 195): violist Franz Weiss and cellist Joseph Linke (Day 289).

For the next performance, Joseph Böhm, the first Professor of Violin at the recently formed Vienna Conservertoire, took over 1st violin. He later recalled:

It was studied industriously and rehearsed frequently under Beethoven’s own eyes: I said Beethoven’s eyes intentionally, for the unhappy man was so deaf that he could no longer hear the heavenly sound of his compositions. And yet rehearsing in his presence was not easy. With close attention his eyes followed the bows and therefore he was able to judge the smallest fluctuations in tempo or rhythm and correct them immediately. (Thayer-Forbes, pp. 940–1)

Joseph Böhm had the idea that new works might be performed twice in a concert. This was tried for Opus 127 on 23 March and 7 April 1825, and the experiment worked. As one critic wrote (as reported in Thayer-Forbes, p. 941):

This professor now performed the wonderful quartet, twice over on the same evening, for the same very numerous company of artists and connoisseurs in a way that left nothing to be desired, the misty veil disappeared and the splendid work of art radiated its dazzling glory.

In his book Beethoven’s Chamber Music, Angus Watson notes that prior to Beethoven’s Opus 127, string quartets were only published as separate parts for the four instruments, making it very inconvenient for someone to study the full score. With Opus 127, Schott published the separate parts as usual, but also a score with all the parts combined,

something which, in general, had not been thought necessary before. The practice was increasing adopted from op. 127 onwards, and spread in later years to include all chamber and orchestral music. (p. 227)

Here is that historic first edition of the complete Opus 127 score.