In summary, Beethoven’s last five string quartets were composed in the following order but anomalously numbered in publication order:

- Opus 127: No. 12 in E♭ major

- Opus 132: No. 15 in A minor

- Opus 130: No. 13 in B♭ major

- Opus 131: No. 14 in C♯ minor

. Opus 135: No. 16 in F major

The first three were composed under commission from Prince Galitzin; the other two were written for music publishers. Some patterns might be evident:

- The quartets alternate in major and minor keys.

- The first and last of this group have a conventional four-movement structure; the middle three have 5, 6, and 7 movements, respectively.

- The middle three have key signatures involving consecutive letters A, B, and C, which might be useful as a mnemonic.

- The final two form a contrasting pair.

Several analysts have explored motific connections between the five quartets. The most ambitious is probably Deryck Cooke’s “The Unity of Beethoven’s Late Quartets” (The Music Review, Vol. 24, pp. 30–49)

After Beethoven had experimented with form and content in the three preceding String Quartets, he retreated into a more conventional structure with Opus 135. This one seems more nostalgic, with the ghosts of Haydn and Mozart hovering around the edges.

Beethoven’s Symphonies 5 and 6 seem to form a contrasting pair, as do Symphonies 7 and 8. So it is also with Beethoven’s Opus 131 and Opus 135 String Quartets. Interestingly, Symphonies 6 and 8 and Opus 135 are all in the key of F major.

Despite the conventional structure and nostalgic feel of the Opus 135 String Quartet, it could never be mistaken for anything other than Late Beethoven. It bursts with surprises, and the wit of the last movement is that of a mature man who has come to terms with life.

Beethoven finished his String Quartet in F major in October 1826, and sent it to music publisher Moritz Schlesinger with the following letter:

Here, my dear friend, is my last quartet. It will be the last; and indeed it has given me much trouble. For I could not bring myself to compose the last movement. But as your letters were reminding me of it, in the end I decided to compose it. And that is the reason why I have written the motto: The decision taken with difficulty — Must it be? — It must be, it must be! (Beethoven Letters No. 1538a)

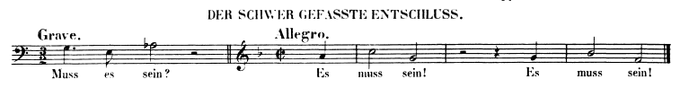

Earlier in the year, Es muss sein had formed the basis of a humorous canon (Day 357). Now together with the original question Muss es sein?, it formed a peculiar title preface preceding the final movement of Opus 135:

Surely Beethoven did not intend this preface to be sung! Yet, he is very deliberately associating two prominent motifs in the last movement with words, embedding the two phrases in our heads so we hear it when the motifs are played.

But do not assume that this curious preface makes Opus 135 the first string quartet with implied lyrics! That honor belongs to Haydn’s string quartet version of his Severn Last Words of Christ from 1787. (In the general case, Haydn always did it first!)

#Beethoven250 Day 361

String Quartet No. 16 in F Major (Opus 135), 1826

The LA-based Viano String Quartet (@vianoquartet) performing in London in a chamber music competition.

The 1st movement of Opus 135 awakens from a slumber with a quirky little motif in its head that it can’t quite shake. The music meanders so effortlessly and with such freedom that we barely notice how exquisitely it’s constructed.

The 2nd movement Scherzo of Opus 135 starts off like a syncopated country dance, but it’s interrupted with sharp staccato chords and other unlikely obtrusions. At one point in the whacky Trio section, the first violin plays a wide leaping crazy dance accompanied by a repeating pattern in the other three instruments that goes on 47 measures.

The sad and lovely 6/8 Lento 3rd movement of Opus 135 is a lullaby theme and four variations. As is common with Beethoven’s more recent theme-and-variation movements, the form is obscured until the second variation, when a change of key and tempo occurs.

The Opus 135 finale begins Grave with a bass singing in F minor Muss es sein? His plight is highlighted by high-pitched screaming chords. The anguish is palpable, and the need to know Muss es sein?

But this is no ordinary slow introduction, for the Allegro that follows not only contradicts the Grave but mocks it! Es muss sein! Es muss sein! it sings in a gleeful F major. You’re being silly with those gloomy epistemological questions. Es muss sein! Es muss sein! The Allegro takes different approaches to reiterating Es muss sein! Es muss sein!, even a delightful little prancing 2nd subject that’s been called a “fairy march.”

The Grave comes back. It still wants to know Muss es sein? The questioner’s straits seem ever more anguished, now accompanied by beseeching high-pitched violin tremolos, but after that mocking Allegro, the Grave seems trapped in some cheesy melodrama.

When the Allegro returns, it’s not quite as insistent. It’s no longer mocking. An understanding has developed. But still it’s obvious and it must be said: Es muss sein.

In a delightful coda, the “fairy march” is played pizzicato, and Es muss sein ends it.